My eulogy for Mum

Thank you to everyone who reached out after my post about Mum’s death. I was overwhelmed with kind and thoughtful responses, so if I haven’t gotten back to you yet, I apologize. I am going to ask your indulgence for just one more post about Mum.

I wrote a short eulogy for her funeral, which I delivered myself (I made it almost to the end without crying), and I want to share it here today as well. The last post was all about her death, but the eulogy is all about her life and who she was, and I can’t resist sharing that with you all too. I found it so comforting after she died to talk to people who knew her about what a remarkable person she was, but I also found I really liked telling stories about her to people who didn’t know her. It is simply very nice to go on and on about Mum, I’m afraid.

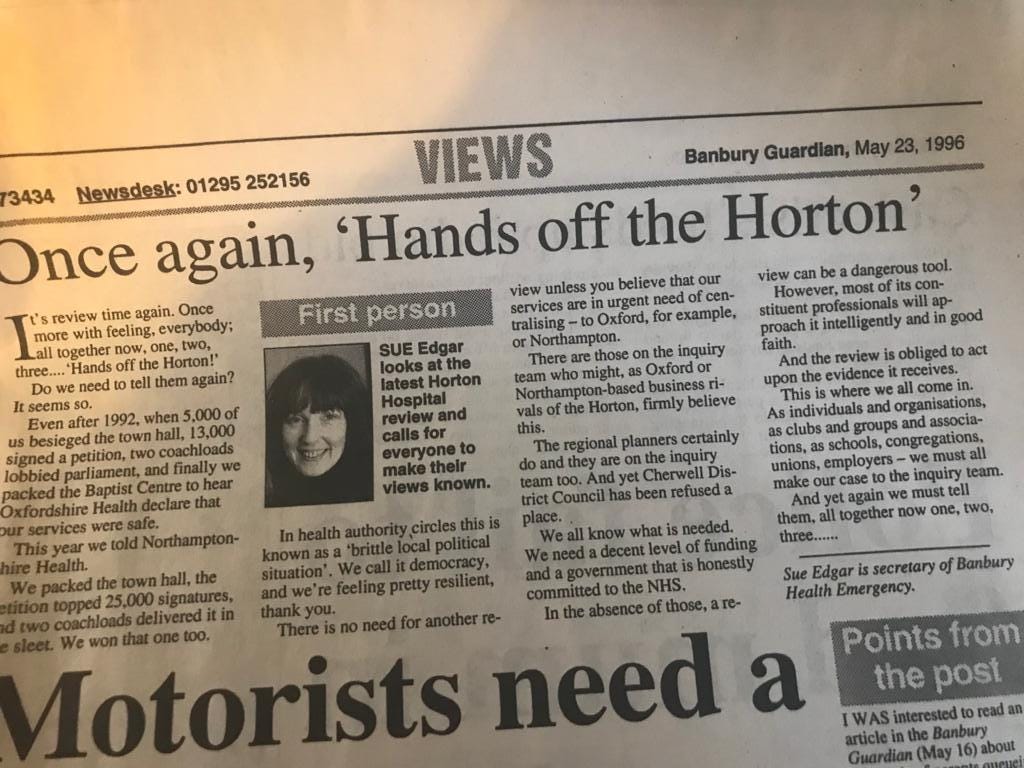

After she died, the local newspaper, the Banbury Guardian, wrote a tribute to her and her work defending the local hospital from closure throughout my life. In fact, they wrote two. I knew all about her activism, of course—somewhere in some newspaper archives in Oxfordshire there’s a picture of me, aged 3 or so, with Mum at a rally to defend the hospital—but it was still inspiring to see it laid out like that. (Obviously, she’s the reason I feel so strongly about healthcare.) Check those pieces out too, if you want.

Thanks again for your patience with these semi-off-topic posts. Next week we’ll be back to normal, with posts about America’s awful healthcare system. For now: One last goodbye to Mum.

My mother, my best friend, is dead—yet I am the luckiest person on Earth, for my mother was Sue Watson. I don’t know how I’ll cope, but then I don’t know how other people cope, never having known her at all. 31 years with Mum is far too short, but so would be one thousand years. We are here to celebrate this extraordinary woman, and thank her for sharing her remarkable self with us.

Mum didn’t shy away from feelings—neither the blissful and beautiful, nor the dark and difficult. She allowed the full joy and anguish of living on Earth into her soul, which is a brave thing to do in a world like ours. She loved music, food, and literature, and had a bottomless capacity to find delight in them. I remember the look on her face when she listened to The National on headphones, and she would press them against her ears so that it was like the music was coming from the center of her head, and there was nothing else in the world—or at least, the droning world outside her could briefly match the vibrance inside her. She could enjoy things more deeply than anyone I’ve known.

But she didn’t guard this deep well of feeling for herself. She was beyond generous, with more presents than you could carry home, and with her attention and her love. She had the truest sense of empathy I’ve ever encountered. She worried about the lives of people on the internet and dogs in viral videos, and she drew real joy from her loved ones’ happiness and success. She could feel for anyone, regardless of who they were. After all, empathy doled out selectively within the bounds of personal morality is just another exercise in vanity, and Mum didn’t have the ability to be vain. She kept every bit of admiration or concern for others, rather than herself.

This capacity for empathy was the foundation of her socialist politics: Her belief in the dignity of every human being, and the absolute necessity of ensuring a good, happy life for all. When she thought about the victims of poverty and inequality that bring shame on our society, she felt real rage and sorrow. Even when it was tiresome, or frustrating, or just unsuccessful, Mum couldn’t shut off her concern for this struggle. She would tell me she was sick of the news and couldn’t pay attention to it anymore, and then an hour later I’d see she’d just retweeted 15 tweets in a row about cuts to benefits and the NHS. She felt injustice deeply, but wouldn’t—and couldn’t—turn her face away and settle into apathy.

When James and I were little, and she would play “This Little Piggy” with us, Mum would change the rhyme from “This little piggy had roast beef/This little piggy had none,” to “This little piggy had roast beef/This little piggy had a Mars Bar.” I can’t remember whether that was all her initiative, or simply that she had already raised us to object, because we all agreed—why on Earth should that little piggy go hungry? (Although the Mars Bar was definitely her pick.) She didn’t hide the cruelty of the world from us, but she did teach us that we shouldn’t accept pain or sadness as a given in life, for ourselves or for other people. That we should be kind, and demand kindness for others. That no one should inevitably be consigned to a lesser life. That everyone should get a Mars Bar.

As kind as she was, she also had an incredible streak of mischief and subversion. She always chose the perfect swear word and deployed it with the correct emphasis. She made rude jokes. She was extraordinarily bright and funny, and particularly found words themselves fascinating and hilarious, and used them better than anyone. She and I had a whole little language together, real words and parodies of words, developed over years of texting. It was an effortless rhythm of communication that was totally unique to us, a constant back-and-forth flow of love and laughter. Looking back at those messages now, it’s clear how I could barely keep up with the pace of her brilliant mind, but I thank her for pretending otherwise.

A couple days after Mum died, I went outside and saw a beautiful sunset, the low clouds ringed with pink gold. I found myself saying hello to Mum, as if she was the sky itself, and telling her I missed her. Not because I believe in an afterlife, or that she’s Looking Down On Me—but because when she was alive, and I saw something beautiful, I would instinctively share it with her. On days when I felt most happy and alive, like the early days of spring, I would gabble to her about the wisteria and the breeze and the sun, my iced coffee and the music I was playing—because I knew she loved to know that I was happy, and I wanted her to know what an incredible life she had given me, but also because she was part of me, and I was part of her. The memory wasn’t whole until it was in both of us.

The existence of beauty and joy in the world is a part of that language I have with her. Now, when I see something beautiful, I reach for the part inside myself where Mum lives. I yearn to show it all to her—I want to tell her something funny about a hundred times a day—but it’s not as lonely as it sounds. She gave me the gift of herself, woven into my experience of everything good on Earth. For as long as there is goodness, Mum will be there, and I will be with her.

What a beautiful tribute to your mum. She sounds like an incredible person and I’m glad she left you with such wonderful memories and ways of seeing beauty, along with pain.

So much beauty and insight in here. Sending love and condolences.